ODDITIES

22 Stories

Lisa Mason

Here You Enter

Yesterday

Tomorrow

& Fantasy

Coming November 17, 2020 in Print and Ebook

ODDITIES

22 Stories

Lisa Mason

Here You Enter

Yesterday

Tomorrow

& Fantasy

Coming November 17, 2020 in Print and Ebook

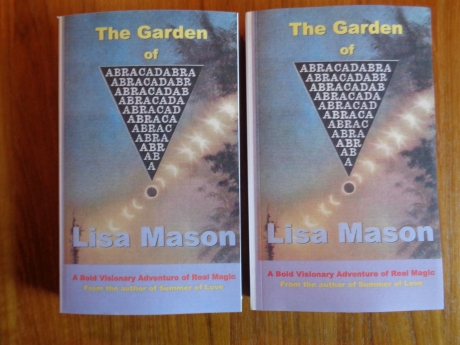

“Crawl Space” is a spin-off from my urban fantasy novel, THE GARDEN OF ABRACADABRA (in print and an ebook). The book is “fun and enjoyable,” as reviewers have commented, while also teaching serious lessons of Real Magic.

Abby Teller, the heroine of the novel, makes a cameo appearance here as well as Esmeralda Tormenta and her companion, Senor (plot spoilers of the novel appear in this story). Nikki Tesla is a regular in the novel and, most of all, the Garden of Abracadabra, a magical apartment building in Berkeley, California near the campus of the College of Magical Arts and Crafts, where Abby has started attending classes.

I hope you’ll take a peek at the novel, which took me two-and-a-half years to write. And a lovely two-and-a-half years, it was.

Crawl Space

Lisa Mason

People often ask, “Jo, how did you get into the plumbing business?”

If I’m feeling flip, I’ll say, “I’m into pipes. Pipes are a girl thing.” If I want to impress, “My mothers founded the business and handed it over to me when they retired. It’s an honorable family tradition.” For a friendly touch, I may add, “Phil taught me how to use her tools when I was a kid. While other girls were playing with dolls and plush animals, I was messing around with P-trap fittings.” If I’ve just filed my quarterly estimated taxes and feeling some pain, I’ll say, “Everybody needs a plumber. You called me, right? That’ll be two-hundred-fifty an hour plus parts.”

Tonight I’m reflective. “My mothers took me to Rome when I was ten. What a trip! We toured the Baths of Caracalla, the Acqua Vergine aqueduct, the Fontana di Trevi. Made quite an impression, y’know?”

“Yeah, all that feminine elemental water energy,” says Abby Teller, the superintendent of the Garden of Abracadabra. Abby landed herself an ideal part-time gig for a student at the Berkeley College of Magical Arts and Crafts. She’s one hell of a super and a crackerjack fledgling magician.

She figured out how to turn off the building’s incoming main when water began cascading through a crack in the ceiling plaster onto her favorite tenant’s means of a livelihood. Then she placed the emergency call to me at eight in the evening just as I was kicking back with a Bud Lite and some brainless dramedy on TV.

Abby has called me more than once to pinch-hit the plumbing problems of these grand old apartments. The Mediterranean building—a leafy walk away from the Magical Arts and Crafts campus—is an architectural treasure built during the gold-rush days and registered by an historical preservation society.

I love the place but things can get dicey there after sunset. Tonight on my way up to Apartment Thirty-nine, for instance, I ran into two of Abby’s other tenants. Esmeralda Tormenta carried a mason jar with a tiny tornado whirling inside it. Her companion, by day a Great Dane named Senor, walked by her side. Since the sun had set, he was wearing his customary red neckerchief (the Great Dane wears the neckerchief, too) and black leather jeans, resembling a youthful Daniel Craig with a scowl and jet-black hair.

Abby says—and who am I to doubt her?—that every one of her tenants is some stripe of supernatural entity, every apartment some kind of fairyland or hell. She told me this, with a weary sigh, the first time she called me. “Will that be a problem for you?”

“Nah, I’m okay with supernatural entities,” I said, desperate for the business.

Abby always pays my bills on time, never bounces a check. When she calls, I come, any day, any night. Abby and me, we’re good.

The tenant says, “Yeah, the Fontana di Trevi is pretty cool. ‘Three Coins in the Fountain.’”

I glance at him, surprised he’d know vintage movies. He looks like a classic computer nerd—but who knows at the Garden of Abracadabra?—with peculiar eyes glowing in his long, bony face, the irises swirling with color like the splash screen of some exotic software. His black hair, bushy eyebrows, and bushier mustache play up his suspicious pallor.

He looms protectively over his computers, printer-scanners, and a serious router with flashing green lights. He’s draped sheets of painter’s plastic over his expensive equipment.

An errant water-drop drips from the ceiling, splats on the plastic.

“Three coins in what?” says the general contractor standing beside the tenant, perplexity on his beefy face. This is the guy Abby calls for dry-wall patches and paint touch-ups.

“Roman tradition says when you toss three coins in the Trevi Fountain, you’ll fall in love and marry,” I explain.

“’Three Coins’ is a sappy romance flick from the nineteen-fifties,” the tenant adds and looks me over.

I’m decked out in my denim jumpsuit and a tool belt with brass hooks and loops of leather. The belt holds a flashlight, three sizes of wrenches and screwdrivers, a metal file, a tube of caulk and a caulk gun, a spray can of Rustoleum, a ball-peen hammer, and a deluxe Swiss Army knife. Tonight I’ve also got a dielectric union with a neoprene gasket dangling from a hook.

The tenant grins in a way that makes my heart go pitter-pat. Blue electrical sparks crackle from his fingertips.

“I got the ceiling opened up like you asked,” the contractor says to Abby and strides to the tenant’s kitchen. “Could we get a move on, please? I’ve got a nine o’clock call in Emeryville.”

In Rome, I’d wandered with Philippa and Theodora around massive stonework walls, vast ancient baths. Theo had turned to me, tears of pride in her eyes, and said, “Think of it, Jo. Plumbers built this.”

I may have been only ten years old but I knew very well that plumbers hadn’t built the Acqua Vergine. Slaves had built it and a master architect had designed it—some guy with an understanding of pre-Christian-era civic water management. Hardly what you’d call a plumber. But I’d held my tongue.

I’d had to do that a lot—hold my tongue—about my mothers, in spite of living in Berkeley. Hold my tongue around them, too. To their gentle unspoken disappointment, I’d turned out to be boy-crazy.

e all trek to the kitchen where the contractor has set up a step ladder to the three-foot hole he’s cut in the ceiling. The contractor and me, we’re not so good. We started off on the wrong foot two jobs ago when he looked at my tool belt and asked, “So where are your handcuffs?”

Phil and Theo had christened their business, “Dominatrix Plumbing.” I could have changed the name when they retired. But they’d built up a clientele, good will, name recognition, and a Better Business Bureau approval rating. Besides, it’s hard to grab people’s attention in Berkeley. “Frank the Plumber” just doesn’t cut it in this town. Flip open the Berkeley phonebook and you’ll find Peace & Love Plumbing, Progressive Sump Pumps, and my fave, Ganga Drains and Sewers.

I couldn’t really resent the contractor but he’s always got this smirky attitude.

He smirks at me now.

After they’d eliminated other possibilities—a rain leak from the building’s roof, tenants upstairs overflowing a water closet or a bathtub—Abby and the contractor decided the problem lies with an interior pipe. A five-point-five earthquake shook up Berkeley last week, and the building is old. Really, really old. Maybe a fitting in the aging galvanized piping has corroded and loosened?

“Water goes wherever it wants to go,” I concur. A plumber’s homily that either boosts a customer’s confidence or irritates the hell out of them.

Both the tenant and the contractor are looking at me like I’m the sacrificial virgin. The astronaut in 2001 fated to go outside the shuttle and fix the propulsion engine banged up by space junk. Or the coon-capped scout sent through enemy musket-fire to deliver a message to the bewigged general at the embattled fort upriver in The Last of the Mohicans. The chosen one, boldly going where no fool has gone before.

When you think about it, our world is made up of two places—private and public. I fix clogged kitchen sinks and leaky bathroom faucets, so I see a lot of private spaces where people keep the messy detritus of their lives deeply rooted within walls and locked doors. I also fix sewers and main drains and travel in my van from job to job, so I see a lot of public spaces, too, where people and creatures and things indiscriminately mingle.

But between the inner wall of private space and the outer wall of the public lies another dimension. In that interstice, elusive electrical cables take harbor, and secret communication connections, hidden heating ducts. Termites, spiders, centipedes, silverfish all call this place their home.

The crawl space.

I climb up the contractor’s step ladder, crawl through the hole, slide on my belly inside.

I switch on my black-and-yellow Dorcy flashlight, sending a beam through the murk. The crawl space is maybe three by three feet. The space smells of centuries-old dust, a tang of mold, a whiff of wood rot. No water on the floor, so Abby’s theory—an isolated interior pipe got knocked askew—seems a good bet.

I spot pipes of red brass, others of yellow brass, and snippets of copper tubing randomly spliced among them. The Garden of Abracadabra needs a plumbing overhaul, big time. I gleefully start calculating estimates. If Phil taught me tools, Theo instilled horse sense. What every independent businesswoman needs to figure poundage per hoof.

The prospect of a Big Job has me smiling when suddenly I shimmy off the edge of a cliff. I plummet with a yell, head over heels, into a deep, dark valley. I land with a splash in a shallow pool of water.

The scattered water-drops reconstitute themselves into the shape of a transparent woman—a water woman, her features discernable on the translucent tension of her watery surface. She smiles seductively and strokes my arm, drenching the sleeve of my jumpsuit. Startled, I instinctively draw the metal file from my tool belt and swipe the file’s edge through her naked waist.

She backs away with a moist smile, cleaved in two, and instantly reconstitutes herself. With a tinkling laugh, she dives into an abyss yawning open before me.

I glance around at the valley, taking in the expanse of dull silver metal studded with cottages of red and yellow brass. The valley stretches away to another cliff rising up in the twilit distance. As I’m gawking, trying to convince myself I haven’t inexplicably died in the crawl space and gone to some hellish plumber’s purgatory, an imposing metal man marches up to me, his boot heels clanking.

“I am King Gob,” he declares and slams his fist on his majestic brass chest with a mighty clang. “Who art thou, wench?”

For a moment, I think he’s called me a “wrench.” Then I realize that isn’t what he said. I’m about to spill my usual intro, “Hi, I’m Jo from Dominatrix, here to whip your plumbing into submission,” but I bite back my words. Between the metal file gripped in my hand like a sword and the scowl on Gob’s brassy face, I cobble a more appropriate response.

I stand up straight, square my shoulders, and somberly say, “I am Josephine, at your service, King Gob.”

“Have ye come to take command of the breach?” he says with enough skepticism to arouse my routine defenses whenever a customer questions my capabilities as a woman plumber.

“I have,” I reply. “Show it to me at once.”

Gob turns and strides away. I follow, warily stepping around the abyss. I glance down into it. Water women cling to the steep sides, laughing mischievously as they slide to the bottom and out through a narrow jagged aperture.

The crack in the tenant’s ceiling plaster? Got to be.

Little silver- and copper-colored children gather shyly in a giggling group, whispering among themselves and pointing at me, their metallic button-eyes wide with wonder.

“Who are you?” I say, smiling.

A brave copper girl steps forward and says, “We’re gobbins of the Valley of Gob, of course.”

“Of course,” I reply politely. “Pleased to meet you.”

“This way,” King Gob says and leads me to the far cliff where a rusted iron step ladder juts out of the rock and ascends to the height of a one-story structure. At the top is a flat service platform. I point my flashlight, illuminating a main line of pipe.

A yellow brass pipe-man extends his brawny arms toward a copper pipe-man. Their metal hands form a perfect circle meant to grasp, to connect one pipe-man to the other.

But their grip has been shaken askew. Their hands don’t quite meet at the intended junction.

As I watch, a water woman oozes between the copper man’s hands and leaps out, dropping on Gob, splashing all over him. The droplets reconstitute and she clings to him, entwining her watery arms around him, staining his joints with a scrim of rust.

He scowls and shouts. But he doesn’t push her away.

I step forward and wipe her off him with my sleeve. She splats on the valley floor and somersaults down the incline toward the abyss, laughing merrily.

“Cursed, cursed undine,” Gob sputters.

I rub the ridges of my metal file on the rust spots the undine left on his joints, abrading them away. “King Gob, why did you not resist her?”

“Oh, we resist the undines as best we can with the quality of metal we’re made of. We confine them when we can, and channel their movements. But undines go where they will.”

“How well I know,” I whisper.

“We cannot control them when they find a way through our channels and barriers.” Gob looks at me, his brass eyes beseeching. “We need a commander of the world like you, Josephine, who can move among undines and gobbins alike.”

I nod. I never thought of myself—me, a plumber!—like that before. But Gob is right. The elements—and their inhabitants, the elementals—are powerful natural forces. They stay within their nature, within their destined path, blindly helping or hindering each other as need or confrontation arises. It takes the eyes and hands and will of a human being to guide and direct all the elements. A human being to rule all the elementals.

That would be me.

Gob glances up at the pipeline. “Can ye repair the breach, Commander?”

“I can,” I say, “and I will.”

I thrust the metal file in my tool belt, climb the rungs of the ladder to the service platform. I step gingerly onto it—it’s flimsier than it looked at a distance—but it holds my weight well enough. I move to the junction of the yellow brass pipe-man and the copper pipe-man. As I survey the breach between their cupped hands, an undine squeezes out, drenches me, and drops to the valley below.

Another undine oozes out and another and another, smiling that seductive smile and laughing merrily. One undine presses her face to mine, another runs her fingers through my hair, still another slips her hands into the sleeves of my jumpsuit.

A shout rises to my throat. Are the undines trying to drown me?

I gulp air, press my lips tight, pinch my nostrils.

For a moment, I feel as if I am drowning. I cannot, I must not drown under their elemental magic. I yank a cotton handkerchief from my hip pocket and wipe the undines off my face, off my jumpsuit. I twist the handkerchief, wringing the cotton out.

The water women drop down onto the gobbins below, pooling on the valley floor, staining their cottages with rust.

“Onward,” I mutter and pull the dielectric union with a neoprene gasket off my tool belt. I fit the gasket over the yellow brass pipe-man’s hands, shove my shoulder beneath the copper pipe-man’s hands, and push their grip into alignment. With the ball-peen hammer, I tamp their connection tightly together. For good measure, I fit the tube of caulk in the gun and smear a layer of sealant around the union.

I climb down the ladder and step amid a cheering crowd of gobbin women and children in shades of red brass and yellow brass and copper.

King Gob beats his fist on his chest and beams at me.

“The breach is secured, at least for the moment,” I announce.

“Thank ye, Commander, we are most grateful,” King Gob says.

“‘Tis but one battle in an ongoing war,” I answer modestly. “The war between order and chaos, law and anarchy, construction and destruction. I am glad to have been of service.”

“Will we see you again?”

“You can count on it.”

The metal king leads me back to the cliff from which I’d so unceremoniously fallen into the Valley of Gob. I climb up the ladder set in the side of it. At the top, I turn and wave grandly to the cheering crowd below me. I look out at the valley, safe from the wanton water, and imagine Theo’s tears of pride, her gentle voice saying, “A plumber did this.”

Yes, she did.

Then I slide on my belly through the crawl space. A centipede scurries out of my way. I find the hole cut in the kitchen ceiling and climb down the contractor’s ladder.

“Geeze, it’s about time,” the contractor says, tapping his finger on his wristwatch. “What took you so long?”

“Did you find the problem?” Abby Teller says.

“I sure did. Two pipes knocked askew, just as you suspected. Yellow brass and copper pipes. They’re incompatible, basically.”

“Any trouble fixing it?”

“Nah, I installed a standard gasket.”

Abby reaches out, touches my head. “Hey, Jo, your hair is wet.”

“Yeah, there was a bit of water up there. The gasket, it’s only temporary. I’ve got to tell you, Abby, the Garden of Abracadabra badly needs the plumbing replaced. Like, all of it. Good copper tubing and solid fittings.”

“I’ll check my budget and let you know when I can schedule the work.”

“Then I’ve got the job?”

“Absolutely.” She shakes my hand, and my whole arm vibrates with her magician’s power. “Got to go. The tenants in Number Eleven and Number Twelve are flinging hexes at each other again. Rival covens, what a hassle.”

She strides out, a tall, slim woman with russet hair. The superintendent of the Garden of Abracadabra, and a pal of mine.

The contractor folds up his ladder. “I’ll be back on Thursday to patch up the ceiling,” he tells the tenant. “Is eight in the evening good for you?”

“It’s going to have to be,” the tenant says with a sigh. “When my girlfriend Tabitha found me with another witch, she cursed me to work every day for the rest of my life from sunrise to sunset at Computers ‘R’ Us. I can only be here, at the Garden of Abracadabra, after the sun goes down.”

“Yeah, right.” The contractor rolls his eyes at me. “Sheesh, Berkeley. The Land of Oz.” He trudges out, lugging the ladder.

I’m left standing in the kitchen with the tenant. We look at each other. A beanpole, he stands head and shoulders above me. Blue sparks flicker from his hands. Oh, boy.

“Can I get you a drink?” he says. “By the way, I’m Nikki Tesla. I’m an electronics wizard.”

“What have you got, wizard?”

“Two percent milk, spring water, vodka, and tonic.”

“Vodka tonic, no ice. Got a lemon or lime?”

“A twist of lime, comin’ up.” Tesla putters around at the kitchen counter, then hands me a cocktail glass. He clinks his glass against mine.

“Oh, wait.” He digs three pennies out of his jeans pocket and tosses them in my glass. “What did you say your name is?”

I squeeze water from my hair. Water and electricity—a dangerous mix. I smile. “Call me Commander Josephine.”

Afterword

For a story barely under 4,000 words, “Crawl Space” packs a lot of plot and took some fairly extensive research. First, there’s THE GARDEN OF ABRACADABRA, of course, which explores in more depth the origin of the apartment building.

Then there’s plumbing. I got out my technical books on how to maintain your home, researched the tools Jo would carry and the tasks she was charged with.

Then there’s Italy and its famous fountains and ancient Roman aqueducts. I found my tourist books and got the right spelling and details of the various landmarks.

And then there’s Berkeley, a famously eccentric college town. A cruise through my telephone book (yes, I still have a paper telephone book) gave me some hints of what Jo and her mothers would name their business.

Finally, I consulted Manly P. Hall’s massive treatise, The Secret Teachings of All Ages, for details about elementals, the spirits that inhabit the elements.

Join my other patrons on my Patreon page at https://www.patreon.com/bePatron?u=23011206.

Leave a tip to the tip jar at PayPal to http://paypal.me/lisamasonthewriter.

Visit me at www.lisamason.com for all my books, ebooks, stories, and screenplays, reviews, interviews, blogs, roundtables, adorable cat pictures, forthcoming works, fine art and bespoke jewelry by my husband Tom Robinson, worldwide links, and more!

Welcome to July, 2020.2! Has it seemed to you like a year has already gone by?

Oops, I’m nearly two weeks late. I’ve got excuses, including a semi-major computer foul-up (I’ll talk about that in another post), but you don’t want to hear excuses.

Over the years, the first two weeks of July have been life-changing for me in many ways. July 2, is the fifth anniversary of our adoption of Athena, after seven and a half catless years from the death of Alana. Friends on Facebook were so taken with my account of changing my mind about never having a cat again, to searching on the Internet, one false start, and then finally finding her. Having to fend off competitors who wanted to adopt her too, to my wild ride to Kitty Hill in Santa Cruz, a real place, and absolutely amazing—that I wrote about the experience, one fantasy level removed from reality. “Crazy Chimera Lady,” a delightful fantasy story will be republished in my upcoming second story collection, ODDITIES, due out this fall.

It goes on. On July 4, my parents married many years ago and 480 moons ago I met Tom Robinson—at a Fourth of July party at my own San Francisco apartment. I had a copy of The Dancing Wu Li Masters, which I was excited about reading, on my coffee table. At midnight, in walked Tom, invited by my neighbor—the illustrator of The Dancing Wu Li Masters. Synchronicity! Quantum physics in real life! On July 7, we married and on July 11 we had our first date. Not in the same year! But we’ve been together ever since.

Strangely, July 11 is also the second anniversary of when I was violently attacked by a man. On a blue-sky summer’s day, I was walking around the lake when the man leapt out of the bushes and attacked me, fracturing my hip in three places and breaking my thigh bone. Two years later, I can walk unaided by a walker or a cane but not very well and not very far.

Two years ago, the moment I woke up from the general anesthetic after three hours of surgery, I had a blazing vision of a memoir, what I wanted to say specifically about the Attack (and I didn’t even yet know ninety percent of what would happen) and more broadly about society and our current troubles. Still confined to bed, I wrote on my laptop a detailed outline, did a solid month’s worth of research, and did a lot of writing. I felt that there would be no cosmic reason that the Attack happened to me other than it was just really bad luck. And that was unacceptable to me. Of all the people walking down the sidewalk that day, the Attack happened to me, a writer.

But it’s been difficult to keep up the momentum and I had to touch on several controversial issues, to which I’ve experienced a lot of hostility on the social media. Tom himself actively opposes my publication of it. So as of today, July 1, I’ve put away all my notes and set the memoir aside for the time being.

God knows, I’ve got enough creative work to do, including working on ODDITIES, plus a third book of the Arachne Trilogy, SPYDER, two more books to finish out the CHROME trilogy plus a prequel novella, a screenplay for an interested producer, and uploading my last two backlist books, PANGAEA I and PANGAEA II. There must be a PANGAEA III to finish out that trilogy. Oh! And at least one other ABRACADABRA book, THE LABYRINTH OF ILLUSIONS.

More stories, a brand-new mystery series set in the 1960s—you get the idea.

Join me on my Patreon page at https://www.patreon.com/bePatron?u=23011206.

Donate a tip to the tip jar at PayPal to http://paypal.me/lisamasonthewriter.

Visit me at www.lisamason.com for all my books, ebooks, stories, and screenplays, reviews, interviews, blogs, round tables, adorable cat pictures, forthcoming works, fine art and bespoke jewelry by my husband Tom Robinson, worldwide links, and more!

At her mother’s urgent deathbed plea, Abby Teller enrolls at the Berkeley College of Magical Arts and Crafts to learn Real Magic. To support herself through school, she signs on as the superintendent of the Garden of Abracadabra, a mysterious, magical apartment building on campus.

She discovers that her tenants are witches, shapeshifters, vampires, and wizards and that each apartment is a fairyland or hell.

On her first day in Berkeley, she stumbles upon a supernatural multiple murder scene. One of the victims is a man she picked up hitchhiking the day before.

Torn between three men—Daniel Stern, her ex-fiance who wants her back, Jack Kovac, an enigmatic FBI agent, and Prince Lastor, a seductive supernatural entity who lives in the penthouse and may be a suspect—Abby will question what she really wants and needs from a life partner.

Compelled into a dangerous murder investigation, Abby will discover the first secrets of an ancient and ongoing war between Humanity and Demonic Realms, uncover mysteries of her own troubled past, and learn that the lessons of Real Magic may spell the difference between her own life or death.

The Garden of Abracadabra is an ebook on BarnesandNoble, Apple, Kobo, and Smashwords.

On Kindle in the U.S., the U.K., Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Netherlands, Japan, Brazil, Canada, Mexico, Australia, and India.

The Garden of Abracadabra is in Print in the U.S., the U.K., Germany, France, Spain, Italy, and Japan.

“So refreshing. . . .This is Stephanie Plum in the world of Harry Potter.”

Goodreads: “I loved the writing style and am hungry for more!”

Amazon.com: “Fun and enjoyable urban fantasy”

This is a very entertaining novel—sort of a down-to-earth Harry Potter with a modern adult woman in the lead. Even as Abby has to deal with mundane concerns like college and running the apartment complex she works at, she is surrounded by supernatural elements and mysteries that she is more than capable of taking on. Although this book is just the first in a series, it ties up the first “episode” while still leaving some story threads for upcoming books. I’m looking forward to finding out more.”

So there you have it, my friends! I’m delighted to announce The Garden of Abracadabra is in print and an ebook worldwide.

Join other patrons on my Patreon page and help me after the Attack. https://www.patreon.com/bePatron?u=23011206. I’ve got delightful new and previously published stories, writing tips, book excerpts, movie recommendations, and more!

Donate a tip in the tip jar at paypal at http://paypal.me/lisamasonthewriter

Visit me at www.lisamason.com for all my books, ebooks, stories, and screenplays, reviews, interviews, blogs, roundtables, adorable cat pictures, forthcoming works, fine art and bespoke jewelry by my husband Tom Robinson, worldwide links, and more!

Please disregard any ad you see here. They have been placed without my permission.

We all could use a laugh these days, so I present for your enjoyment “Transformation and the Postmodern Identity Crisis”. The story was commissioned by editor Margaret Weis and published in the anthology Fantastic Alice, New Stories from Wonderland by Ace Books. The story was republished in my first story collection, Strange Ladies: 7 Stories by Bast Books. Here are what of the some of the critics say about the collection:

“Offers everything you could possibly want, from more traditional science fiction and fantasy tropes to thought-provoking explorations of gender issues and pleasing postmodern humor…This is a must-read collection.”

—The San Francisco Review of Books

“Lisa Mason might just be the female Philip K. Dick. Like Dick, Mason’s stories are far more than just sci-fi tales, they are brimming with insight into human consciousness and the social condition….a sci-fi collection of excellent quality….you won’t want to miss it.”

—The Book Brothers Review Blog

“Fantastic book of short stories….Recommended.”

—Reader Review

“I’m quite impressed, not only by the writing, which gleams and sparkles, but also by [Lisa Mason’s] versatility . . . Mason is a wordsmith . . . her modern take on Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland is a hilarious gem! [This collection] sparkles, whirls, and fizzes. Mason is clearly a writer to follow!”

—Amazing Stories

Transformation and the Postmodern Identity Crisis

I want to thank you all for inviting me here tonight to this, the thirtieth anniversary of my Fall into Wonderland. Yes, thank you, thank you very much. I would never have come if the Dodo hadn’t promised there’d be a fat speaker’s fee in it for me.

It’s not as though any of you have kept in touch. It’s not as though you’ve given me a jingle just to say, “How’s tricks, Alice?” It’s not as though you give a sh—oh, I beg your pardon. I don’t mean to offend. It’s not as though you’ve got the slightest notion what I’ve been through all these years.

Whatever happened to Alice, you want to know? She was, after all, such a strange little girl. Ever a scowl. Ever a snippy word. Had herself an attitude.

What could I do, what else was I fit for, after Wonderland? Of course I became a writer as my big sister encouraged me to do. You should see how much money I owe her. Oh, but you’ve never heard of me. You’ve never seen me on the list of the top ten richest writers in the world. You’ve never seen a trilogy of movies based on my books.

What are my books? Surely you’ve read The Shapeshifters, Down and Out in Berkeley and Boston, and TartGate: the Swindle and Tea-tray. Thank you, thank you very much. You congratulate me. How glamorous, Alice, you say. How exciting! What an adventure!

Have you got the slightest notion how the publishing business works these days?

One slaves in solitude over a book for two or three years, compromising health, sanity, and financial security. One’s editor pays an advance that covers the bills for two or three months, not counting food, phone service, and lottery tickets. One’s book gets noticed for two or three weeks. Booklist is snide, TLS brutal. After production costs, printing, paper, binding, marketing expenses, and general overhead to keep the publisher in posh digs, one earns two or three cents in royalties. One’s book is remaindered in two or three days while one’s editor implores one to get off that lazy bum and write ten more before the year-end.

Never mind the fantasies of hanging oneself. These will pass.

Who would ever aspire to a literary career? One would have to be raving mad.

But you don’t care. That’s on me, you say. Get a job. You don’t give a sh—oh, I beg your pardon. I don’t mean to suggest you’re an insensitive dullard who would rather veg out in front of the tellie every night than read a good book now and then. You don’t want to hear about the troubles of a girl of forty. The compulsive weaving of daisy-chains. The soporifics acquired without a prescription. The anonymous encounters in seedy laundromats with persons who refuse to make change. The arrests for disorderly conduct in tony shopping malls during lunch hour. Oh well, you say. You’re an Artist, Alice. Drowning in one’s own sorrow. It’s in the cards.

You want to romanticize Wonderland. You want to hear how cool it was. What a rave. What a romp. What a beneficent influence Falling into Wonderland had on my life. How Wonderland transformed me.

Transformed us all.

Have you got the slightest notion what happened to the White Rabbit? Every advantage, that’s what he had. Got admitted to Harvard Law School. Graduated summa cum laude. Joined the blue-chip law firm of O’Hare & Leporiday. Made partner in five years. White-collar crime and commodities fraud his speciality.

Yet there was always something too precious, too fussbudgety, about him. I suppose we should have seen it coming when the White Rabbit became an animal rights activist. Joined Small Mammals Against Savage Humans. Stands in SMASH picket lines outside Saks Fifth Avenue every Saturday, flinging ketchup on ladies in fur coats. Frequents the petting zoo every Sunday. Travels round the country delivering speeches supporting cruelty-free cosmetics dressed in a Givenchy gown, spike heels, and full makeup.

His poor old mum, whom you never hear about, nearly had a stroke when he posed, shaved bald and nude, for the cover of Vanity Fair. She calls me. “Where did I go wrong?” she wants to know. “Every advantage, that’s what he had.”

“Exactly, mum,” I tell her. “It’s postmodern life. Life after Wonderland. None of us knows who we are anymore.”

You’re silent now. Not chuckling? Not applauding? Do I suggest that the White Rabbit’s youthful experiences underground had some bearing upon his wantonness later in life? Do I suggest that Wonderland was an incitement to explore the dangerous depths of the subconscious mind? An inducement to abandon the moral strictures and conventions that Society, our schools, and our families have struggled so mightily and with the best of intentions to impose upon us?

In exchange for what? Illicit freedom?

Uncommon nonsense, you say? Ridiculous? Paranoid?

Well. It makes no difference to me if the White Rabbit pickets KFC franchises dressed in a chicken suit, but his law partners didn’t feel the same way. Hounded him out of the firm. Of course he’s suing. His mum won’t speak to him. And he still frequents the petting zoo every Sunday. You may draw your own conclusions.

But that’s the White Rabbit, you say. The White Rabbit is a shining example of the Dr. Spock generation. Those coddled Boomer kids. Me yesterday, Me tomorrow, and Me today. Give ‘em what they want when they want it. Every advantage, that’s what they’ve had. And see how they turn out?

Have you got the slightest notion what happened to the Mock Turtle? There’s another casualty. Diagnosed schizophrenic with delusions of bovinity. But since when has mental illness ever interfered with stardom? Since when has delusion ever impeded huge fame?

Those big brown eyes, that throbbing tenor raised in song! The sighs, the sobs. The disingenuous self-pity, the sudden sulking silences. Those maudlin dance tunes! What tabloid on the grocery store checkout stand hasn’t told the tale of how he became the idol of millions overnight? Mock Turtle, the King of Sop.

Of course Wonderland left its mark on him. I only became aware of how deeply damaged he was when we dated ten years later. The Mock Turtle is not exactly a fellow you want to introduce to your mum. But when we met again on the beach at Mazatlan, I fell for him hard. Always was a soft touch for his Poor Me act. One day he took me to a Miami Dolphins game. We stood up for the pledge of allegiance to the flag, and what do you suppose he said?

“A wedge of lemon in my glass

Of salt-rimmed tequila;

And with my French fries dipped in lard,

One burger

In a bun

With mustard and relish for all.”

Eating disorder, nothing. Obsessed with food, he was! Always crooning about soup and fish sticks. A foodaholic, a gourmand in extremis. A skinny reptile struggling to get out of that shell. Food fetishes? Try peanut-butter-and-bacon sandwiches. Couldn’t get through the day without a box of Ritz crackers. No wonder he packed on the pounds. Heart attack material, that’s what he became. And that’s what did the Mock Turtle in. Right in the middle of a performance on a Las Vegas soundstage. That’s the truth—it was a coronary. Not the booze, the pills, the teenage girls.

Of course everyone knows the consumption of mood-altering substances was commonplace in Wonderland. The mysterious liquids in those little stoppered bottles. The cakes of unknown ingredients left out on a side table. The smoke twisting up from herbaceous tinder. Could one contend that the fungus which induced the sensation of growing larger or smaller actually altered the body, such as steroids do? Or merely altered the mind? Though plenty of body-altering there. Take one’s liver, for starters. Never mind one’s brain cells. But oh so good, as the song goes. Can you imagine enduring the rat race without coke and Jack on the rocks? No wonder so many of us in postmodern society seek consolation in chemicals.

Who can blame us, after Wonderland?

To read the rest of the popular humorous story and discover whatever happened to the Caterpillar, the King and Queen of Hearts, the Gryphon, the Cheshire Cat and other denizens of Wonderland, please go my Patreon page at https://www.patreon.com/bePatron?u=23011206. You’ll find new and previously published stories, book excerpts, writing tips, movie recommendations, and more exclusively for patrons.

Meanwhile, check out Strange Ladies: 7 Stories (“A must-read collection—The San Francisco Review of Books). On Nook, Smashwords, Apple, and Kobo.

On Kindle at US Kindle, Canada Kindle, UK Kindle, Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Brazil, Japan, India, Mexico, and Netherlands.

Strange Ladies: 7 Stories is in Print in the U.S., in the U.K., in Germany, in France, in Spain, in Italy, and in Japan.

Visit me at www.lisamason.com for all my books, ebooks, stories, and screenplays, beautiful covers, reviews, interviews, blogs, roundtables, adorable cat pictures, forthcoming works, fine art and bespoke jewelry by my husband Tom Robinson, worldwide links, and more!

Updated for 2020! Published in print in seven countries and as an ebook on eighteen markets worldwide.

As I mulled over my published short fiction (now forty stories), I found seven wildly different stories with one thing in common–a heroine totally unlike me. I’m the girl next door. I have no idea where these strange ladies came from.

In The Oniomancer (Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine), a Chinese-American punk bicycle messenger finds an artifact on the street. In Guardian (Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine), an African-American gallerist resorts to voodoo to confront a criminal. In Felicitas (Desire Burn: Women Writing from the Dark Side of Passion [Carroll and Graf]), an immigrant faces life as a cat shapeshifter. In Stripper (Unique Magazine), an exotic dancer battles the Mob. In Triad (Universe 2 [Bantam]), Dana Anad lives half the time as a woman, half the time as a man, and falls in love with a very strange lady. In Destination (Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction), a driver takes three strangers from a ride board on a cross-country trip as the radio reports that a serial killer is on the loose. In Transformation and the Postmodern Identity Crisis (Fantastic Alice [Ace]), Alice considers life after Wonderland.

Five stars on Facebook and Amazon! “Great work, Lisa Mason!”

“Hilarious, provocative, profound.”

From Jeanne-Mary Allen, Author on Facebook and the Book Brothers Blog: “Kyle Wylde and I are thrilled to have found such a talented, dedicated, and brilliant collection of shorts in Strange Ladies: 7 Stories…Your style/craft is highly impressive.”

From the San Francisco Book Review: “Strange Ladies: 7 Stories offers everything you could possibly want, from more traditional science fiction and fantasy tropes to thought-provoking explorations of gender issues and pleasing postmodern humor…This is a must-read collection.” http://anotheruniverse.com/strange-ladies-7-stories/

From the Book Brothers Review Blog: “Lisa Mason might just be the female Philip K. Dick. Like Dick, Mason’s stories are far more than just sci-fi tales, they are brimming with insight into human consciousness and the social condition….Strange Ladies: 7 Stories is a sci-fi collection of excellent quality. If you like deeply crafted worlds with strange, yet relatable characters, then you won’t want to miss it.” http://www.thebookbrothers.com/2013/09/the-book-brothers-review-strange.html#more

And on Amazon: 5.0 out of 5 stars This one falls in the must-read category, an appellation that I rarely use.

“I have been a fan of Lisa Mason from the beginning of her writing career, but I confess that I often overlook her short fiction. That turns out to have been a big mistake! I have just read Strange Ladies thinking I would revisit a few old friends and discover a few I had missed. Well, I had missed more than I had thought, and I regret that oversight. This collection was so much fun! I loved each and every story and enjoyed their unique twists, turns, and insights. I thank Ms Mason especially, though, for the high note ending with the big smiles in Transformation and the Postmodern Identity Crisis. Uh oh, I guess I still am a child of the summer of love. Well played. You made me laugh at the world and myself.”

From Amazing Stories. com “I’m quite impressed, not only by the writing, which gleams and sparkles, but also by [Lisa Mason’s] versatility . . . Mason is a wordsmith . . . her modern take on Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland is a hilarious gem! [This collection] sparkles, whirls, and fizzes. Mason is clearly a writer to follow!”—Amazing Stories

5.0 out of 5 stars Great collection that will make you think

Format: Kindle Edition

“My definition of a good short story is one that you keep thinking about for days, and this book had several of them.”

Strange Ladies: 7 Stories (“A must-read collection—The San Francisco Review of Books). On Nook, Smashwords, Apple, and Kobo.

On Kindle at US Kindle, Canada Kindle, UK Kindle, Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Brazil, Japan, India, Mexico, and Netherlands.

Strange Ladies: 7 Stories is in Print in the U.S., in the U.K., in Germany, in France, in Spain, in Italy, and in Japan.

Join my Patreon page at https://www.patreon.com/bePatron?u=23011206 and help me while I recover from the Attack. I’ve got delightful new stories and previously published stories, books excerpts, writing tips, movie recommendations, and more there for you with more on the way.

Visit me at www.lisamason.com for all my books, ebooks, stories, and screenplays, worldwide links, beautiful covers, reviews, interviews, blogs, round-tables, adorable cat pictures, forthcoming works, fine art and bespoke jewelry by my husband Tom Robinson, and more!

At her mother’s urgent deathbed plea, Abby Teller enrolls at the Berkeley College of Magical Arts and Crafts to learn Real Magic. To support herself through school, she signs on as the superintendent of the Garden of Abracadabra, a mysterious, magical apartment building on campus.

She discovers that her tenants are witches, shapeshifters, vampires, and wizards and that each apartment is a fairyland or hell.

On her first day in Berkeley, she stumbles upon a supernatural multiple murder scene. One of the victims is a man she picked up hitchhiking the day before.

Torn between three men—Daniel Stern, her ex-fiance who wants her back, Jack Kovac, an enigmatic FBI agent, and Prince Lastor, a seductive supernatural entity who lives in the penthouse and may be a suspect—Abby will question what she really wants and needs from a life partner.

Compelled into a dangerous murder investigation, Abby will discover the first secrets of an ancient and ongoing war between Humanity and Demonic Realms, uncover mysteries of her own troubled past, and learn that the lessons of Real Magic may spell the difference between her own life or death.

The Garden of Abracadabra is an ebook on BarnesandNoble, Apple, Kobo, and Smashwords.

On Kindle in the U.S., the U.K., Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Netherlands, Japan, Brazil, Canada, Mexico, Australia, and India.

The Garden of Abracadabra is in Print in the U.S., the U.K., Germany, France, Spain, Italy, and Japan.

“So refreshing. . . .This is Stephanie Plum in the world of Harry Potter.”

Goodreads: “I loved the writing style and am hungry for more!”

Amazon.com: “Fun and enjoyable urban fantasy”

This is a very entertaining novel—sort of a down-to-earth Harry Potter with a modern adult woman in the lead. Even as Abby has to deal with mundane concerns like college and running the apartment complex she works at, she is surrounded by supernatural elements and mysteries that she is more than capable of taking on. Although this book is just the first in a series, it ties up the first “episode” while still leaving some story threads for upcoming books. I’m looking forward to finding out more.”

The Garden of Abracadabra was, in part, inspired by the Garden of Allah, a townhouse and apartment complex in Hollywood, California. New Yorker writers, like Robert Benchley and Dorothy Parker and F. Scott Fitzgerald, who went to L.A. to write screenplays, and actors like the Marx Brothers and Errol Flynn lived it up there and created quite a scandalous reputation for the place. “Big Yellow Taxi,” the song by Joni Mitchell was inspired when the city razed the place to the ground and built a strip mall over the ruins. “They paved Paradise and put up a parking lot,” the line goes.

So there you have it, my friends! I’m delighted to announce The Garden of Abracadabra is in print and an ebook worldwide.

Join other patrons on my Patreon page and help me after the Attack at https://www.patreon.com/bePatron?u=23011206. I’ve got delightful new and previously published stories, writing tips, book excerpts, movie recommendations, and more for patrons!

Visit me at www.lisamason.com for all my books, ebooks, stories, and screenplays, reviews, interviews, blogs, roundtables, adorable cat pictures, forthcoming works, fine art and bespoke jewelry by my husband Tom Robinson, worldwide links, and more!

Please disregard any ad you see here. They have been placed without my permission.

At her mother’s urgent deathbed plea, Abby Teller enrolls at the Berkeley College of Magical Arts and Crafts to learn Real Magic. To support herself through school, she signs on as the superintendent of the Garden of Abracadabra, a mysterious, magical apartment building on campus.

She discovers that her tenants are witches, shapeshifters, vampires, and wizards and that each apartment is a fairyland or hell.

On her first day in Berkeley, she stumbles upon a supernatural multiple murder scene. One of the victims is a man she picked up hitchhiking the day before.

Torn between three men—Daniel Stern, her ex-fiance who wants her back, Jack Kovac, an enigmatic FBI agent, and Prince Lastor, a seductive supernatural entity who lives in the penthouse and may be a suspect—Abby will question what she really wants and needs from a life partner.

Compelled into a dangerous murder investigation, Abby will discover the first secrets of an ancient and ongoing war between Humanity and Demonic Realms, uncover mysteries of her own troubled past, and learn that the lessons of Real Magic may spell the difference between her own life or death.

The Garden of Abracadabra is an ebook on BarnesandNoble, Apple, Kobo, and Smashwords.

On Kindle in the U.S., the U.K., Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Netherlands, Japan, Brazil, Canada, Mexico, Australia, and India.

The Garden of Abracadabra is in Print in the U.S., the U.K., Germany, France, Spain, Italy, and Japan.

“So refreshing. . . .This is Stephanie Plum in the world of Harry Potter.”

Goodreads: “I loved the writing style and am hungry for more!”

Amazon.com: “Fun and enjoyable urban fantasy”

This is a very entertaining novel—sort of a down-to-earth Harry Potter with a modern adult woman in the lead. Even as Abby has to deal with mundane concerns like college and running the apartment complex she works at, she is surrounded by supernatural elements and mysteries that she is more than capable of taking on. Although this book is just the first in a series, it ties up the first “episode” while still leaving some story threads for upcoming books. I’m looking forward to finding out more.”

So there you have it, my friends! I’m delighted to announce The Garden of Abracadabra is in print and an ebook worldwide.

Join other patrons on my Patreon page and help me after the Attack. https://www.patreon.com/bePatron?u=23011206. I’ve got delightful new and previously published stories, writing tips, book excerpts, movie recommendations, and more for patrons!

Visit me at www.lisamason.com for all my books, ebooks, stories, and screenplays, reviews, interviews, blogs, roundtables, adorable cat pictures, forthcoming works, fine art and bespoke jewelry by my husband Tom Robinson, worldwide links, and more!

Please disregard any ad you see here. They have been placed without my permission.

This is an ebook adaptation of Lisa Mason’s novelette, “The Sixty-Third Anniversary of Hysteria,” published in Full Spectrum 5 (Bantam). A Postscript and a list of Research Sources follow.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

A Bast Book

Copyright 2012 by Lisa Mason.

All rights reserved.

PUBLISHING HISTORY

Bast Books ebook edition published March 2012

Praise for Books by Lisa Mason

Strange Ladies: 7 Stories

“Offers everything you could possibly want, from more traditional science fiction and fantasy tropes to thought-provoking explorations of gender issues and pleasing postmodern humor…This is a must-read collection.”

—The San Francisco Review of Books

“Lisa Mason might just be the female Phillip K. Dick. Like Dick, Mason’s stories are far more than just sci-fi tales, they are brimming with insight into human consciousness and the social condition….a sci-fi collection of excellent quality….you won’t want to miss it.”

—The Book Brothers Review Blog

“Fantastic book of short stories….Recommended.”

—Reader Review

“I’m quite impressed, not only by the writing, which gleams and sparkles, but also by [Lisa Mason’s] versatility . . . Mason is a wordsmith . . . her modern take on Lewis Carrol’s Alice in Wonderland is a hilarious gem! [This collection] sparkles, whirls, and fizzes. Mason is clearly a writer to follow!”

—Amazing Stories

Summer of Love, A Time Travel

A San Francisco Chronicle Recommended Book of the Year

A Philip K. Dick Award Finalist

“Remarkable. . . .a whole array of beautifully portrayed characters along the spectrum from outright heroism to villainy. . . .not what you expected of a book with flowers in its hair. . . the intellect on display within these psychedelically packaged pages is clear-sighted, witty, and wise.”

—Locus Magazine

“A fine novel packed with vivid detail, colorful characters, and genuine insight.”

—The Washington Post Book World

“Captures the moment perfectly and offers a tantalizing glimpse of its wonderful and terrible consequences.”

—The San Francisco Chronicle

“Brilliantly crafted. . . .An engrossing tale spun round a very clever concept.”

—Katharine Kerr, author of Days of Air and Darkness

“Just imagine The Terminator in love beads, set in the Haight-Ashbury ‘hood of 1967.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“Mason has an astonishing gift. Her characters almost walk off the page. And the story is as significant as anyone could wish. This book will surely be on the prize ballots.”

—Analog

“A priority purchase.”

—Library Journal

The Gilded Age, A Time Travel

A New York Times Notable Book

A New York Public Library Recommended Book

“A winning mixture of intelligence and passion.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“Should both leave the reader wanting more and solidify Mason’s position as one of the most interesting writers in science fiction.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Rollicking. . .Dazzling. . .Mason’s characters are just as endearing as her world.”

—Locus Magazine

“Graceful prose. . . A complex and satisfying plot.”

—Library Journal

Celestial Girl, The Omnibus Edition (A Lily Modjeska Mystery)

Passionate Historical Romantic Suspense

5 Stars “I really enjoyed the story and would love to read a sequel! I enjoy living in the 21st century, but this book made me want to visit the Victorian era. The characters were brought to life, a delight to read about. The tasteful sex scenes were very racy….Good Job!”

—Reader Review

The Garden of Abracadabra

“So refreshing! This is Stephanie Plum in the world of Harry Potter.”

—Goodreads Reader

“Fun and enjoyable urban fantasy….I want to read more!”

—Reader Review

“I love the writing style and am hungry for more!”

—Goodreads Reader

The Sixty-third Anniversary of Hysteria

Diary

6 May 1941. We’ve arrived at last after months in Casablanca, which I once remembered fondly & now loathe. Sold all my good white linen bed sheets for Moslem shrouds to raise money for our sea passage. The Faithful must meet their Maker wrapt in the colour of purity, but I would’ve slept on straw, on mud, on a bed of nails to leave Africa.

Every day we were in danger. Everyone knows B.B. supported the Loyalists in Spain & wrote editorials for La Revolution Surrealiste & corresponded with Trotsky, for godssake. Fascists in every bar & café. Nazis, too, now that Rommel has taken over the Occupation & his officers carouse their days away. The Soviets will make mincemeat of you within the year, B.B. told anyone who would listen. Didn’t care a fig who listened in. Every night I feared the knock on our door, which thankfully never came.

As for our sea passage, I have little to record. I was sick, B.B. was sick. Everyone sick & absolutely grey with fear. We sailed on a Union Oil tanker, The Montebello. A favorite sport of Nazi U-boats, torpedoing a merchant ship with refugees aboard. No more than a rifle or two to defend us, should we be attacked. Every day the radio told of another sinking–in the Atlantic, in the Caribbean, & all hands lost. Nazi U-boats take no prisoners, save no survivors bobbing amongst the waves. I began to wonder what it must be like to drown. Your hair streaming up into sunlit waters, your feet plunging into blackness below. The fearsome struggle to breathe–would it be swift or slow? Would you notice fish? When would they start nibbling at the lobes of your ears?

I had to set this journal aside. Force myself to stop conjuring up horrors.

When we hobbled ashore at Tampico, I fell on my knees & kissed the beach. I mean literally. B.B. laughing & lurching about on his sea legs. I can still taste the sand on my lips. Filthy, but marvelous. The marvelous taste of our deliverance.

Nothing but the shirts on our backs & two little bags between us. We haven’t got a penny.

It’s completely true what Breton says of our destination.

Mexico is the Surrealist place par excellence. The land blazes with a savage golden light. A tiger light. The jungle spreads its tendrils to the very edge of town & the leaves of certain palms possess a clarified green the like of which I’ve never seen in Britain nor in Europe, save perhaps Tuscany. Blossoms have their wanton way in every window box, on every street corner, through every crevice in the ancient stone walls. Brick & mortar are no match for the lusty thrust of Life. I love the lascivious pinks, the regal purples. I spied a scarlet that actually throbbed, as if the colour of blood was pulsing from a newly opened wound. The natives wear their modernity lightly. As if civilization is but a garment to be donned or disposed of at one’s will.

I should like to feel that unencumbered of my past.

Thanks to the small refugee stipend paid to us by the Mexican government, we have found an apartment on Gabino Barreda, near the Monument to the Revolution (B.B. likes that, a poetic touch). Three horrid little rooms in a decaying stucco tenement. Plaster crumbling off the walls, scorpions in the kitchen. Other vermin, too, I fear. Mother would faint dead away at the sight of the pit in the floor that passes for our indoor plumbing. There is an alcove off the bedroom, though, which has light nearly all day & a terrace overlooking the street, which is delightfully picturesque. B.B. says I may take it for my art studio. The landlady (upon whom B.B. has worked his usual masculine charms) came by with two white, blue-eyed kittens, brushstrokes of fawn on nose & paw. She says they are Sealpoint Siamese such as I have not seen since Mother’s house in London.

Enchanting & I wept, realising how much I’ve left behind. How much the war has taken from us. The simple pleasure of kittens.

How can I not be happy?

Mexico City

“To the late Doctor Sigmund Freud,” says Gunther, raising his shot glass in a toast.

“To the great and monstrous Id,” says Enrique.

“To the Sixty-third Anniversary of Hysteria,” says Wolfie.

“Hear, hear,” adds B.B., a bit anemically. Poor man, he is not well.

Cheers ring out all round. Nora raises her glass as a courtesy, too weary to cheer. Tequila spills over her fingers, stinging the cut on her thumb she’d got unpacking B.B.’s papers. He needed everything ready by morning so he could start work on his new play. While he’d slept like the dead, she had labored long into the night. Their two bags no longer seeming so little or so sparse of belongings.

Nora knows these three merry fellows from Paris during her café days. Gunther and Wolfie are a pair of Hungarians, Enrique a Greek. Now they are all displaced Surrealists. A new nationality of their own. The tropical climate suits them, Nora is pleased to see. Gunther has grown positively stout on rice and beans, Wolfie sports an alarming mustache, and Enrique, well. Enrique is ever Enrique, a sly smile wrapped around a cigarette. Now he wears a jaunty straw hat and a white linen shirt, having retired his black Basque beret to a drawer along with his black wool scarf.

Exiles in Mexico City they all are, this ragged gang of painters, poets, and pundits. They’ve fled from everyplace a Nazi boot has kicked in a door or threatened to. Hungarians and Swedes, Austrians and Russians, British and Spanish and French. The Mexicans and Peruvians–Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Cesar Moro–serve as centers of gravity for these wayward comets. If not for the war, half these visionaries and rabble-rousers would scarcely be on speaking terms with the other half. But the war, now safely far behind them on the Continent, has taught strange and marvelous tricks to a pack of aging mongrels.

Gunther flings tequila into his throat, chases away the sting with a gulp of black beer. B.B., always one to follow suit around his comrades, flings a shot and gulps, as well, though flamboyant gestures do not become him. Never a robust man, B.B. has weathered the war rather badly. He has been leached and winnowed into something peevish and frail, his finely made face worn-out with worry. His hair has ebbed to the top of his skull, exposing the enigmatic dome of his forehead. Ever the intellectual, B.B. has assumed such an intense introspective air that people pause around him, even when he’s liquored up, and await an oracle.

“To Freud? How passé.” A woman’s voice, ironic, incisive, cuts through the male bombast and swoops into Nora’s eager ear. “Still stuck on nasty old Sigmund, what a pity.”

Valencia sweeps into the parlour of her house, smiling in her ironic way. She plucks the shot glass from Nora’s hand, offers a tumbler rimmed in salt. “Try this instead, cherie. Lime and tonic, with crushed ice. A much better way to sample tequila for the first time. We are not barbarians like Gunther and your poor old B.B.”

Nora, a little nervous, reacquaints herself with another famous face from the Paris days. Valencia, always towering, has transformed herself here into an Amazon queen, voluptuous and formidable. She wears her fiery chestnut hair in an unkempt mane that tumbles around her face and down her shoulders. Her bold Spanish features are much as Nora recalls. The huge dark eyes, the left one slightly askew. The rapier snout of a conquistador. Bee-stung lips of a shady lady. Altogether a splendid face, if not exactly pretty.

“Valencia, hello again,” Nora says, taking the tumbler. “Thanks ever so. You look marvelous.”

“You, too, cherie. Though a little frazzled around the edges, eh? Still, ever our English beauty. Drink up.”

Nora plucks at her threadbare blouse, abashed. You never could tell if Valencia was taking aim or only skewering your own self-doubts. If Valencia is an Amazon, Nora is a fairy-queen. Queen of the gnats. So petite and unassuming, few ever notice her, despite her pretty face and lustrous sable curls. The war has worn her down, too. She is much too thin, much too pale. Bad food, days brooding belowdecks, and despair have bleached all the colour from her English cheeks. Fleeing Fascism is fashionable only in theory. This she has learned the hard way.

Nora slides the tart taste of lime down her throat. Thirsty, so very thirsty. For refreshment. For friendship. Mexico City sits at the top of the world. They say the air is always bone-dry.

They say the Kahlo-Rivera circle is an arid place, too, harboring much public animosity toward correspondents of Trotsky like B.B. Not that Nora ever wrote to the famous revolutionary herself. She’s just an artist. But she shall surely be painted by the same brush by Frida and Diego.

Suddenly B.B. is at her side, gripping her elbow. Solicitous, fatherly, though of course they are lovers, he takes her tumbler. “I don’t think she should,” he says to Valencia.

Who regards his gesture with narrowed, glinting eyes. Tigress eyes.

“You are having a drop yourself, B.B.,” Valencia observes.

“Yes, but I am ever the drunkard. Whereas my little Nora hasn’t touched drink in ages, not the whole time we were exiled in Casablanca.” He sets her tumbler on a side table. And that’s that, in B.B.’s scheme of things. “Be so good as to tell me what is wrong with Freud, Madam Valencia?”

“Hah! Tell me what is right about Freud.”

She sweeps Nora under her arm, reclaiming the tumbler as she goes and restoring it to Nora’s hand. “You must come and see my art studio, cherie.”

Nora shrugs and rolls her eyes at B.B., who is scowling. What can she do, swept away by a force of nature?

Valencia and her husband Renato own a house on Via del Rosa Moreno, five blocks west of Nora and B.B.’s apartment. No horrid little rooms or crumbling plaster for Valencia. Renato has money. The place is a palace. Whitewashed ceilings, Moroccan arches, great expanses of floor paved in terra cotta tile. There is an interior garden with a fountain. Valencia’s art studio, which opens onto the garden, has an adobe fireplace and native grotesqueries displayed on the walls. There is an Olinala jaguar mask with genuine fangs. A Michoacán devil mask, post-Cortez, bearing a striking resemblance to a Satan of Catholic inspiration. A Tlacozotitlan bat mask, a jungle nightmare held aloft by carved wood wings.

Nora is dazzled. But then Valencia has always dazzled everyone. They met among the clique surrounding Andre Breton and Yves Tanguy. Valencia slept with the great men, one after another. Breton himself had noticed her since she, sloe-eyed and slender then, was the sort of femme-enfant he craved like candy. Plus, she possessed unbeatable cachet: Valencia was a budding Surrealist artist. She painted interior landscapes. The shadows of the subconscious mind whirled and writhed across her haunting canvases.

Nora had been awed by Valencia then, too, and not a little envious. She had slept with too many of the less-than-great men, with the too-beautiful poet who wound up preferring gin and boys, and she was still painting competent Italian countrysides. Olive trees and Etruscan ruins, what rot. Nora hadn’t yet discovered how to paint past her eye. How to explore the depths of pure imagination.

Now Valencia is the great woman with whom lesser men are privileged to dine in Mexico City. For the great men like Breton and Tanguy have had the means and connections to escape the ravages of Europe in New York City. In the years since Paris, Valencia has become well-known in Surrealist circles, if not to the larger public. Peggy Guggenheim shows her paintings at Guggenheim Jeune Gallery. Valencia has collectors. Not many, but enthusiastic. And rich.

Among the canvases stacked in the studio, Nora spies a painting of a sphinx. She stoops for a closer look. Not the Egyptian monument nor the ripe she-beasts of Louis XIV statuary, but a vixenish creature with tabby-cat’s paws and a child’s face. The creature crouches in a decaying mansion, toying with a human jawbone, broken eggshells, a tidbit of bloody meat.

Something jars Nora, gazing at this strange image. Something takes her back to Mother’s house, the great rooms deserted. Everyone had gone to church, and a cousin, a rawboned boy fifteen years to her ten, stood towering over her. There were eggs. Eggs she’d dropped on the floor beneath her knees, and a whitish scum smeared across the tiles. A whitish scum lingering in her mouth.

No, that didn’t happen. You were dreaming, darling, Mother said when she stammered out her story. Cousin came with us to church. Cook must have dropped the eggs.

“Valencia, this is smashing,” she says, shaken. “I’ve never seen anything like it. Is this a new direction for you?”

Valencia starts to answer, then presses her finger to her lips, for now the men are strolling into the art studio, laughing and bickering. Tequila fumes rise off them, an alcoholic miasma. Nora bites back her words, cut off from further conversation. Well, but of course, it’s a party. B.B. hooks his elbow around her neck, as he often does, dangling his forearm across her collarbone. His hand hanging over her heart.

“So, Valencia, my dear, have you seen much of Frida and Diego lately?” Gunther says.

“No, not much at all. Watch your step, gentlemen, that canvas took me four months of heart-wrenching work. Rivera is in poor health, you know. Frida attends to his every need, as if he were still a little boy in his nappies.”

The men trade uneasy glances. Some of them revere Rivera, some despise him, but all consider the internationally famous, famously charming, and charismatic artist to be some kind of deity visiting this poor mundane world at his leisure. Valencia’s gibe makes them fidget, Nora observes, even if they suspect it’s true. Yet who can object? Valencia knows Kahlo and Rivera better than any of them. She is–what is the American expression?–she is in the know.

“Come now, ma belle, Valencia,” says B.B. Ah, Nora thinks, here it comes. “You have not set out for us your objections to Doctor Freud. The greatest analyst of the human mind in our times.”

“Oh, my, haven’t I?” A wink for Nora. And a little twisting motion with her fingers beside her lip, as if she were a Spanish gentleman adjusting his mustache. Very disconcerting to the gentlemen present.

“You have not,” B.B. asserts, assuming his lordly professorial air. Though he’s weaving on his feet.

“Well, to start, Freud hated women,” Valencia says, laughing as though this is quite a joke.

“Oh, that is not true, Valencia,” Gunther says. “The great doctor spent hours and hours with his madwomen.”

“Didn’t he, though,” says Enrique with his sly smile.

“You are all absurd,” B.B. says in such a commanding, condescending tone that he silences everyone. “It is Freud, madam, who first explicated the existence and causes of l’amour fou attitudes passionelles. The supreme means of ecstatic expression at which you women are so adept.” At that, he peers at the painting of the sphinx.

“Ah, Hysteria,” Valencia says. “The divine madness of women.”

“To the Sixty-third Anniversary of Hysteria,” Wolfie says, less clearly, and raises another toast of tequila. He cradles the bottle in the crook of his arm.

“Now, Wolfie,” Valencia begins. Taking aim, indeed. “Do you wish to live forever in the shadow of Breton? As for me, I’m still annoyed by the Fiftieth Anniversary of Hysteria. An event rather in questionable taste, even for Surrealists, don’t you think? How like Breton, publishing photographs of those poor lunatics at Salpetriere Hospital. As an artistic statement! All of them women, of course, in psychotic fugue and various stages of undress. You’d rather have your women mad than freethinking, eh, B.B.?”

Nora waits, breathless, for her lover’s answer.

“I agree, the quality of the photographs was rather poor,” he replies in a mild tone. “But Breton’s lack of talent as a publisher is not the point. Come now, admit it, Valencia. Sigmund Freud was the first man in history to truly understand women.”

“And what did Freud understand, pray tell?”

“Why, that women are the link to the subconscious mind.”

“Whose subconscious mind?” Valencia says. She clarifies, “The subconscious mind of whom?”

“Don’t be obtuse, Valencia,” B.B. says. “Freud exalts Woman. She is the link to the Id of the Artist. To the darkness. To the lurking dirtiness. She disturbs the Poet, and She compels him. She penetrates his every inhibition. She unleashes his forbidden desires, oh yes. She is the key, the trigger, the perfumed bomb. She is that onto which his passions may be projected. She is his fantasy, and his fantasy fulfilled.”

“A blank slate, is that what you mean, B.B.? An empty vessel with no thoughts or talents of her own?”

“She is my Muse,” B.B. says. He squeezes Nora’s neck so tightly she winces in pain.

“Dear old B.B. So dependent on women, after all.” Her glinting eyes turn to Nora. “And what about you, cherie? Is he your key, your trigger? How does he compel you when you paint your vision?”

Nora blushes. She has no answer.

“As for me,” Valencia declares, “I am my Muse.”

Diary

22 June 1941. V. has changed my life. We see each other nearly every day. Teacher, soul-sister, friend. Muse, indeed, for she challenges me to look beyond the surface of the world. To look deep within myself & my imagination. To view our Art as a Calling & a Quest, not merely decoration for the rich.

Gossipmonger, too. V. is filled with talk about things going on everywhere. A spider tugging at each strand of her web for juicy morsels. How I adore it! She claims Kahlo has such a mustache on her lip from pleasing Rivera too much. You know what I mean. Certain prostitutes on the Rue de G develop the same problem, she says, with a twist of her imaginary mustache. I don’t know if this could possibly be true, but it makes for an awfully nasty rumor. Kahlo is a tragic figure, of course, with her grievous injury & her beautiful tortured paintings & having to cater to Rivera with his temper & his mistresses. Yet as much as I do truly pity her, I find her theatrical & intimidating & have not sought out her company, nor she mine. In any case, B.B. disapproves of her & Diego, but that’s politics.

V. studies a Swiss psychoanalyst, one Carl Jung. Once Freud’s disciple, Jung was cast out of his circle over theoretical/political dissension. V. adores Jung almost as much as she despises Freud. Jung is on to something when he talks about the subconscious, V. says. Rather than the repository of eroticism & primitivism (as Freud would have it), the subconscious (for Jung) is the repository of occult wisdom & magical powers. “Magical powers” being a metaphor for one’s inner strengths & talents. Jung does not actually believe magical powers exist, does he?

Like Freud, Jung believes the subconscious is essentially female. Intuition feminine, too. If this is so, then Woman is not only erotic, but also occult.

V. is deeply moved by these ideas. I’m much taken, too, but not quite sure what to believe. (I read V.’s books in her art studio. Don’t dare bring them home, should B.B. find them & throw them in the trash.)

Yesterday at the market V. & I found a plant with strange, egg-like fruit. We didn’t know what it was, had never seen such a thing before. V. told me to run & fetch my brushes & bring them to her studio, which I did, posthaste. We placed the plant in her garden & arranged my brushes around it. V. claimed the light of the full moon would fall upon everything & the Alchemical Egg would bless my brushes with creative power. Together we composed & then recited an incantation & danced like dervishes & drank a liter of red wine, all of which I found quite amusing. V. assured me this is not frivolous, this is inspiration. This is Magic. Lord, I will try anything to overcome this block of mine.

On my way home I found a tiny bird’s nest which had fallen to the pavement. A sticky little ball of twigs & spider silk & tucked inside, an egg no larger than a gumdrop. I picked the nest up & placed it in the crotch of a lemon tree next to the sidewalk. The very moment I did this, mother hummingbird flitted up & hovered, as if in thanks, blinking at me with her tiny beady bird eyes. I prayed: Oh Alchemical Egg, give birth to Me.

Silly, I know, but there you are & I was so happy, thinking this is a very good omen.

Started pencil sketches for a new painting tonight. My first work in Mexico City: a woman curled up inside of an egg.

Mexico City

Nora is exhausted by the time she arrives home from the advertising agency. The downtown bus was running late, she’s been running a fever for a week, there is nothing decent in the cupboard for dinner, and, to top it off, B.B. is in a foul mood again.

“Where have you been?” he snaps as she drags in the door.

“At work, of course,” she snaps back.

“At Valencia’s again,” he says. On principle, he cannot object to her friendship with the great Surrealist Artist, but he chafes at her devotion to her friend just the same.

“At work,” she repeats. “And at Valencia’s,” softening her tone, for what is the use of quarreling with B.B.? “I wanted to visit the cats.”

Nora could not afford to keep the Siamese kittens, who have transformed themselves into sleek little chocolate-cheeked panthers. Valencia, who is such a cat lover that friends have nicknamed her Felina, gladly them took in, but it’s discouraging. Nora cannot afford to keep cats. Nora cannot afford much more than their rent, rice, and beans. She cannot afford new shoes. She lines the insides of her once-fine Italian leather pumps with newspaper. She cannot afford a new blouse. She washes perspiration stains out of the weary old cotton with lye soap and a scrub brush. The advertising agency is pleased with her projects, simple but energetic pen-and-ink drawings extolling the virtues of aspirin and hair tonic, but they only pay for piecework, which amounts to little.

B.B., on the other hand, does not work in any gainful way. After losing his family’s house and land in Vienna to the Nazis, he has been paralyzed with grief though–Nora reminds herself–he never worked in any gainful way before then, either. He is unable to face the daily stringency of reporting to an office. He feels he does not speak Spanish well enough to translate or write for a local newspaper.

In any case, he’s started the new play. How can I write for a newspaper, he wants to know, if I’m to write the new play? Sometimes Nora thinks B.B. would be content to live in the streets and beg for food, all for the sake of the new play. Still, the play is his salvation. Everything he lives for. If not for the play, he tells her, I would have hanged myself a year ago.

This frightens her, this talk of hanging himself. Nora has loved B.B. for years. She reveres him. He was a great man, a poet and a playwright respected in Paris, in all of Europe, by Breton himself, an entire decade before she met him. She, his young lover, cannot possibly allow B.B. to live in the streets and beg for food. Let alone hang himself.

Still, there is the troublesome fact that he has written nothing significant in the year after their exile and flight. Oh, a page or two since the day she unpacked his papers upon arriving in Mexico City. She must be patient, she tells herself. He’s returning to his work, thanks to her. You‘re all I have left in the world, he tells her. You are my Muse.

“Did you get cigarettes? Tequila?” he growls now. Tobacco and booze fuel him. He must have cigarettes and tequila if he is to write the new play.

“I forgot we were out.”

Nora has hidden cigarettes in her little art studio for herself, for the hard-won moments when she can be there, painting. Her secret stash, which she refuses to share. Having to work has considerably slowed progress on her new painting. Yet Nora goes to the advertising agency and takes in sewing when she can because she would not be content to live in the streets and beg for food. She must at least have rice and beans. At the least the apartment on Gabino Barreda. She can do without new shoes and new blouses, but she must have paint. She must have canvases.

“Well, give me some money,” he says, “and I’ll go fetch everything.”

She gives him the last of her money for the week, and he goes out in search of cigarettes and tequila. She washes her hands and her face in the washbasin in the corner. Still mopping her neck with a towel, she drifts to his desk.

His work is put away, as usual, or covered up with a sheet of blank paper. He has not felt ready to show her the play, he says, and she respects that, the fragility of a new creation. She twinges with guilt at violating his orders not to disturb his things, but she’s not disturbing anything, she’s merely peeking. She picks up his ashtray, which needs emptying, anyway, and observes he has left a sheet of paper in his typewriter. Out of carelessness, his hangover, or deliberately, she cannot be sure. There, on the half-typed page she reads:

JUSTINE

I beg you, Master! Please, not again, I cannot bear it!

MASTER

(chaining her left ankle to the bedpost)

Yes, again, my little love. One day you will beg me for it.